Astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope have for the first time precisely measured the distance to one of the oldest objects in the universe, a collection of stars born shortly after the big bang.

This new, refined distance yardstick provides an independent estimate for the age of the universe. The new measurement also will help astronomers improve models of stellar evolution.

Star clusters are the key ingredient in stellar models because the stars in each grouping are at the same distance, have the same age, and have the same chemical composition. They therefore constitute a single stellar population to study.

This stellar assembly, a globular star cluster called NGC 6397, is one of the closest such clusters to Earth. The new measurement sets the cluster’s distance at 7 800 light-years away, with just a 3% margin of error.

Until now, astronomers have estimated the distances to our galaxy’s globular clusters by comparing the luminosities and colours of stars to theoretical models, and to the luminosities and colors of similar stars in the solar neighborhood. But the accuracy of these estimates varies, with uncertainties hovering between 10 percent and 20%.

However, the new measurement uses straightforward trigonometry, the same method used by surveyors, and as old as classical Greek science.

Using a novel observational technique to measure extraordinarily tiny angles on the sky, astronomers managed to stretch Hubble’s yardstick outside of the disk of our Milky Way galaxy.

The research team calculated NGC 6397’s age at 13,4-billion years old. “The globular clusters are so old that if their ages and distances deduced from models are off by a little bit, they seem to be older than the age of the universe,” says Tom Brown of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, leader of the Hubble study.

Accurate distances to globular clusters are used as references in stellar models to study the characteristics of young and old stellar populations.

“Any model that agrees with the measurements gives you more faith in applying that model to more distant stars,” Brown says. “The nearby star clusters serve as anchors for the stellar models.

“Until now, we only had accurate distances to the much younger open clusters inside our galaxy because they are closer to Earth.”

By contrast, about 150 globular clusters orbit outside of our galaxy’s comparatively younger starry disk. These spherical, densely packed swarms of hundreds of thousands of stars are the first homesteaders of the Milky Way.

The Hubble astronomers used trigonometric parallax to nail down the cluster’s distance. This technique measures the tiny, apparent shift of an object’s position due to a change in an observer’s point of view.

Hubble measured the apparent tiny wobble of the cluster stars due to Earth’s motion around the Sun.

To obtain the precise distance to NGC 6397, Brown’s team employed a method developed by astronomers Adam Riess, a Nobel laureate, and Stefano Casertano of the STScI and Johns Hopkins University, to accurately measure distances to pulsating stars called Cepheid variables. These pulsating stars serve as reliable distance markers for astronomers to calculate an accurate expansion rate of the universe.

With this technique, called “spatial scanning,” Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 gauged the parallax of 40 NGC 6397 cluster stars, making measurements every six months for two years. The researchers then combined the results to obtain the precise distance measurement.

“Because we are looking at a bunch of stars, we can get a better measurement than simply looking at individual Cepheid variable stars,” says team member Casertano.

The tiny wobbles of these cluster stars were only 1/100th of a pixel on the telescope’s camera, measured to a precision of 1/3000th of a pixel. This is the equivalent to measuring the size of an automobile tire on the moon to a precision of one inch.

The researchers say they could reach an accuracy of 1% if they combine the Hubble distance measurement of NGC 6397 with the upcoming results obtained from the European Space Agency’s Gaia space observatory, which is measuring the positions and distances of stars with unprecedented precision. The data release for the second batch of stars in the survey is in late April.

“Getting to 1% accuracy will nail this distance measurement forever,” Brown says.

The team’s results appeared in the March 20, 2018, issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The research team consists of T Brown, S Casertano, and D Soderblom (STScI); J Strader (MSU); A Riess and J Kalirai (STScI, JHU); D VandenBerg (UVic); and R Salinas (Gemini).

When you want to know the size of a room, you use a measuring tape to calculate its dimensions.

But you can’t use a tape measure to cover the inconceivably vast distances in space. And, until now, astronomers did not have an equally precise method to accurately measure distances to some of the oldest objects in our universe – ancient swarms of stars outside the disk of our galaxy called globular clusters.

Estimated distances to our Milky Way galaxy’s globular clusters were achieved by comparing the brightness and colors of stars to theoretical models and observations of local stars. But the accuracy of these estimates varies, with uncertainties hovering between 10 percent and 20 percent.

Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers were able to use the same sort of trigonometry that surveyors use to precisely measure the distance to NGC 6397, one of the closest globular clusters to Earth. The only difference is that the angles measured in Hubble’s camera are infinitesimal by earthly surveyors’ standards.

The new measurement sets the cluster’s distance at 7,800 light-years away, with just a 3 percent margin of error, and provides an independent estimate for the age of the universe. The Hubble astronomers calculated NGC 6397 is 13.4 billion years old and so formed not long after the big bang. The new measurement also will help astronomers improve models of stellar evolution.

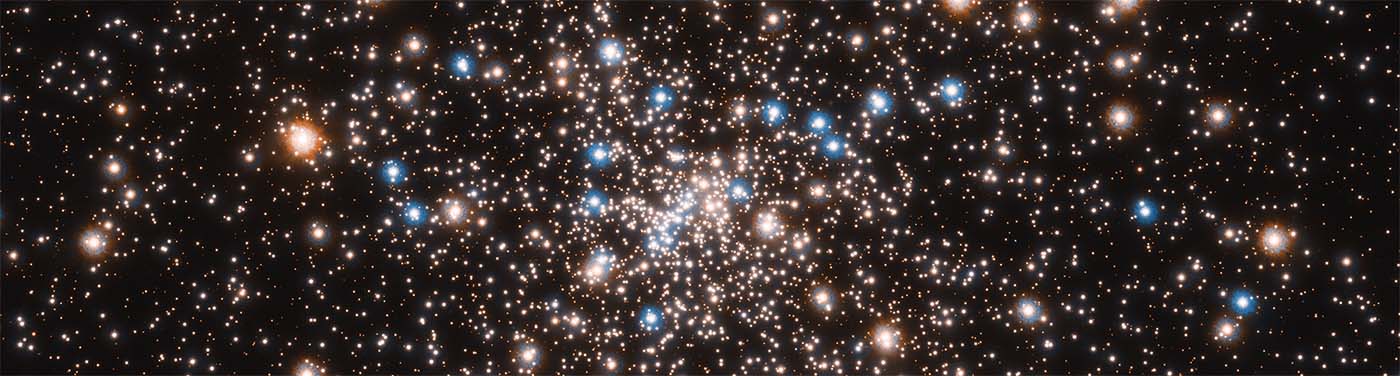

Pictured: This ancient stellar jewellery box, a globular cluster called NGC 6397, glitters with the light from hundreds of thousands of stars.

Credits: NASA, ESA, and T. Brown and S Casertano (STScI)