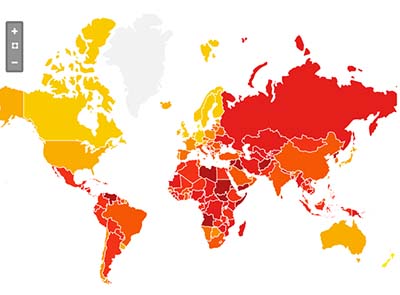

South Africa has been placed at number 64 on the latest Corruption Index, with an overall score of 45%.

This compares to top-placed Denmark with a score of 90% and bottom-placed Somalia with just 10%.

According to Corruption Index author Transparency International, this year’s results highlight the connection between corruption and inequality, which feed off each other to create a vicious circle between corruption, unequal distribution of power in society, and unequal distribution of wealth.

“In too many countries, people are deprived of their most basic needs and go to bed hungry every night because of corruption, while the powerful and corrupt enjoy lavish lifestyles with impunity,” says José Ugaz, chair of Transparency International.

The lower-ranked countries in the index are plagued by untrustworthy and badly functioning public institutions like the police and judiciary, according to Transparency Internationa. Even where anti-corruption laws are on the books, in practice they’re often skirted or ignored.

People frequently face situations of bribery and extortion, rely on basic services that have been undermined by the misappropriation of funds, and confront official indifference when seeking redress from authorities that are on the take.

Higher-ranked countries tend to have higher degrees of press freedom, access to information about public expenditure, stronger standards of integrity for public officials, and independent judicial systems. But high-scoring countries can’t afford to be complacent, either.

While the most obvious forms of corruption may not scar citizens’ daily lives in all these places, the higher-ranked countries are not immune to closed-door deals, conflicts of interest, illicit finance, and patchy law enforcement that can distort public policy and exacerbate corruption at home and abroad.

Transparency International’s Paul Banoba, in his analysis on sub-Saharan Africa, says elections held across the continent in 2016 provide a good reflection of corruption trends in the region.

“In countries like Ghana, which is the second worst decliner in the 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index in the region, the dissatisfaction of citizens with the government’s corruption record was reflected in their voting at the polls.

“South Africa, which continues to stagnate this year, has witnessed the same. Joseph Kabila’s Democratic Republic of Congo and Yahya Jammeh’s Gambia, which both declined, demonstrate how electoral democracy is tremendously challenged in African countries because of corruption.”

Good news for the region includes Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, the most improved African countries in the 2016 index. Both countries held democratic presidential elections in 2016.

“It is no surprise that the independent electoral observer teams labelled the Cape Verde elections for 2016 as ‘exemplary’,” writes Banoba. “This election that saw Jorge Carlos Fonseca re-elected, was held in a framework of a continuously improving integrity system, as observed by various African governance reviews.”

In São Tomé and Príncipe elections held in July 2016 led to a smooth change of government, which is increasingly a challenge in the African region.

On the other hand, despite being a model for stability in the region, Ghana, together with another six African countries, has significantly declined.

“The rampant corruption in Ghana led citizens to voice their frustrations through the election, resulting in an incumbent president losing for the first time in Ghana’s history,” according to Banoba.

Some other large African countries have failed to improve their scores on the index. These include South Africa, Nigeria, Tanzania and Kenya.

“South African President Jacob Zuma was in court and in the media for corruption scandals,” Banoba says. “This included his own appeal against findings in a report by the Public Prosecutor Thuli Madonsela, regarding undue public spending in his private homestead in Nkandla.”

Kenya – despite the adoption of a few anti-corruption measures including passing a law on the right to information – has a long way to go, he adds. “President Uhuru expressed frustration that all his anti-corruption efforts were not yielding much. He may need new strategies as Kenyan citizens go to the polls in 2017.”

Right at the bottom of the list is Somalia, whose parliamentary elections were marred by malpractice and corruption, and whose presidential elections were postponed three times last year and are yet to be held.

What needs to happen, says Banoba, is that African leaders that come to office on an “anti-corruption ticket” will need to live up to their pledges to deliver corruption-free services to their citizens. T

“hey must implement their commitments to the principles of governance, democracy and human rights. This includes strengthening the institutions that hold their governments accountable, as well as the electoral systems that allow citizens to either re-elect them or freely choose an alternative.”