NASA is sending a helicopter to Mars.

The Mars Helicopter, a small, autonomous rotorcraft, will travel with the agency’s Mars 2020 rover mission, currently scheduled to launch in July 2020, to demonstrate the viability and potential of heavier-than-air vehicles on the Red Planet.

“NASA has a proud history of firsts,” says NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. “The idea of a helicopter flying the skies of another planet is thrilling. The Mars Helicopter holds much promise for our future science, discovery, and exploration missions to Mars.”

Started in August 2013 as a technology development project at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the Mars Helicopter had to prove that big things could come in small packages.

The result of the team’s four years of design, testing and redesign weighs in at little under four pounds (1,8kg). Its fuselage is about the size of a softball, and its twin, counter-rotating blades will bite into the thin Martian atmosphere at almost 3 000 rpm – about 10 times the rate of a helicopter on Earth.

“Exploring the Red Planet with NASA’s Mars Helicopter exemplifies a successful marriage of science and technology innovation and is a unique opportunity to advance Mars exploration for the future,” says Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at the agency headquarters in Washington.

“After the Wright Brothers proved 117 years ago that powered, sustained, and controlled flight was possible here on Earth, another group of American pioneers may prove the same can be done on another world.”

The helicopter also contains built-in capabilities needed for operation at Mars, including solar cells to charge its lithium-ion batteries, and a heating mechanism to keep it warm through the cold Martian nights.

But before the helicopter can fly at Mars, it has to get there. It will do so attached to the belly pan of the Mars 2020 rover.

“The altitude record for a helicopter flying here on Earth is about 40 000 feet. The atmosphere of Mars is only one percent that of Earth, so when our helicopter is on the Martian surface, it’s already at the Earth equivalent of 100 000 feet up,” says Mimi Aung, Mars Helicopter project manager at JPL. “To make it fly at that low atmospheric density, we had to scrutinise everything, make it as light as possible while being as strong and as powerful as it can possibly be.”

Once the rover is on the planet’s surface, a suitable location will be found to deploy the helicopter down from the vehicle and place it onto the ground. The rover then will be driven away from the helicopter to a safe distance from which it will relay commands. After its batteries are charged and a myriad of tests are performed, controllers on Earth will command the Mars Helicopter to take its first autonomous flight into history.

“We don’t have a pilot and Earth will be several light minutes away, so there is no way to joystick this mission in real time,” says Aung. “Instead, we have an autonomous capability that will be able to receive and interpret commands from the ground, and then fly the mission on its own.”

The full 30-day flight test campaign will include up to five flights of incrementally farther flight distances, up to a few hundred meters, and longer durations as long as 90 seconds, over a period.

On its first flight, the helicopter will make a short vertical climb to 3m, where it will hover for about 30 seconds.

As a technology demonstration, the Mars Helicopter is considered a high-risk, high-reward project. If it does not work, the Mars 2020 mission will not be impacted. If it does work, helicopters may have a real future as low-flying scouts and aerial vehicles to access locations not reachable by ground travel.

“The ability to see clearly what lies beyond the next hill is crucial for future explorers,” says Zurbuchen. “We already have great views of Mars from the surface as well as from orbit. With the added dimension of a bird’s-eye view from a ‘marscopter,’ we can only imagine what future missions will achieve.”

Mars 2020 will launch on a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, and is expected to reach Mars in February 2021.

The rover will conduct geological assessments of its landing site on Mars, determine the habitability of the environment, search for signs of ancient Martian life, and assess natural resources and hazards for future human explorers. Scientists will use the instruments aboard the rover to identify and collect samples of rock and soil, encase them in sealed tubes, and leave them on the planet’s surface for potential return to Earth on a future Mars mission.

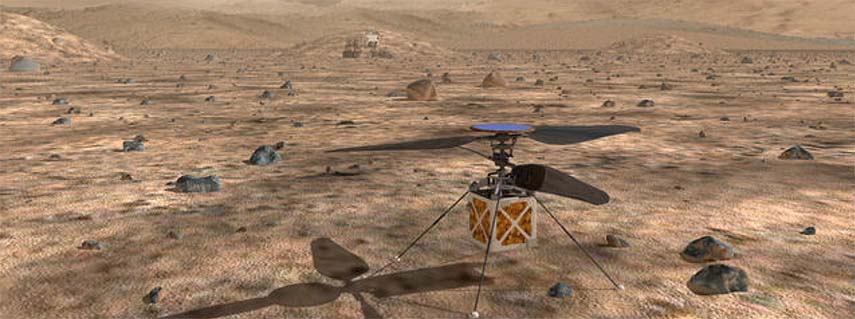

Pictured: NASA’s Mars Helicopter, a small, autonomous rotorcraft, will travel with the agency’s Mars 2020 rover, currently scheduled to launch in July 2020, to demonstrate the viability and potential of heavier-than-air vehicles on the Red Planet.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech