Ice fronts have retreated, rocky peaks are more exposed, fewer icebergs drift to the ocean: the branching network of glaciers that empty into Greenland’s Sermilik Fjord has changed significantly in the last half century.

Comparing Landsat images from 1972 and 2019, those changes and more come into view.

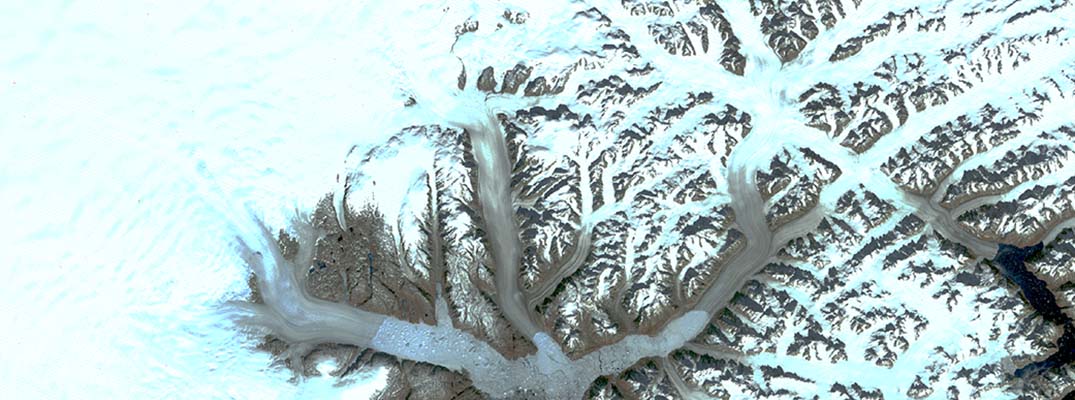

Glaciers in southeastern Greenland including, from left, Helheim, Fenris and Midgard are seen in a Landsat 8 image from Aug. 12, 2019 (right image), and a composite image from Landsat 1 scenes collected in September 1972 (left image). Comparing images across the span of the Landsat mission provides a record of almost five decades of change to this region of southeast Greenland.

Credits: NASA/Christopher Shuman

The glaciers appear brownish grey in this true-colour Landsat 8 satellite image from 12 August 2019.

The colour indicates that the surface has melted, a process that concentrates dust and rock particles and leads to a darker recrystallised ice sheet surface.

The darker melt surface in 2019 extends much further on to the ice sheet than it did in 1972, when the first Landsat satellite gathered data on the area, says Christopher Shuman, a glaciologist with the University of Maryland at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Landsat is a joint mission of NASA and the US Geological Survey.

Helheim Glacier, one of the largest and fastest flowing of its kind in Greenland, has retreated approximately 7,5km up a wide fjord in the time between the two scenes, leaving a jumble of sea ice where its calving front used to be.

To the east, Midgard Glacier has retreated approximately 16km, splitting into two branches farther up the fjord. Changes to the rocky outcrops of the area’s mountains and smaller tributary glaciers are also visible by comparing the two Landsat images.

The Helheim Glacier is seen in a close-up of the images above. One of the largest glaciers in Greenland, Helheim has retreated approximately 4.7 miles (7.5 kilometers) between when these Landsat scenes were collected in 1972 (left image) and 2019 (right image). As the glacier lost ice over the last 47 years, the cliff walls along the glacier and the rocky outrcrops in the middle become more exposed.

Credits: NASA/ Chris Shuman

“There’s a lot more bare rock visible now, which used to be covered with ice,” Shuman says. “And all these little glaciers are all getting slammed, as well as the bigger ones like Helheim, Fenris and Midgard. There are scores of examples of change just in this one area.”

In a close-up of the Helheim Glacier, a patch of open water is visible right at the calving front.

Three days after Landsat 8 collected the image over Helheim and its neighboring glaciers, NASA’s Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) project flew over that open patch of water in an airplane and dropped a temperature-measuring probe that detected warm water at the ice front.

OMG is examining how oceans melt glaciers from below, even as air temperatures warm the ice from above.

NASA’s Oceans Melting Greenland campaign flew over a region of open water at the calving front of Helheim Glacier on Aug. 15, 2019, dropping a temperature probe that detected warm water. The open water is visible in the 2019 Landsat image above.

Credits: NASA /Josh Willis

Unusually warm air temperatures this summer have caused record melt across Greenland. Approximately 90% of the surface of Greenland’s ice sheet melted at some point between 30 July 30 and 2 August, during which time an estimated 55 billion tons of ice melted into the ocean, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Centre.

Shuman also tracked the unusual warm weather at the top of the Greenland Ice Sheet, 3 216m above sea level, where temperatures were above freezing for more than 16,5 hours total during 30 July and 31 July.