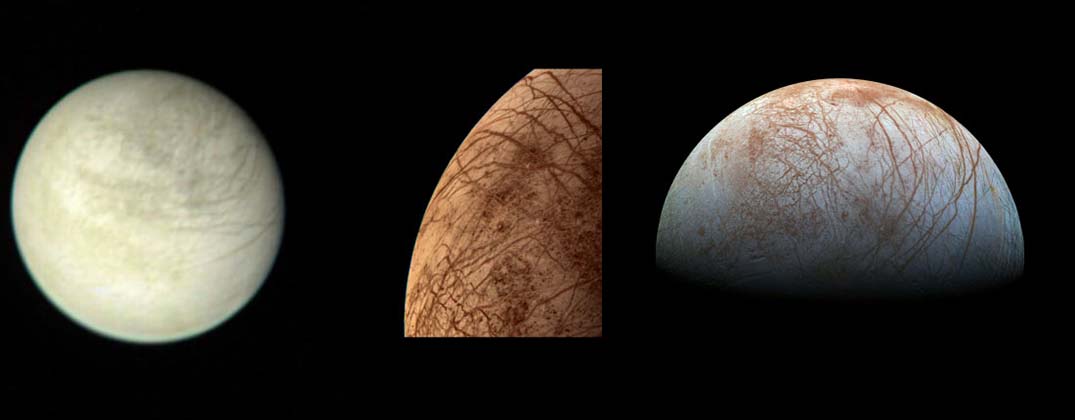

Forty years ago, a Voyager spacecraft snapped the first closeup images of Europa, one of Jupiter’s 79 moons. These revealed brownish cracks slicing the moon’s icy surface, which give Europa the look of a veiny eyeball.

Missions to the outer solar system in the decades since have amassed enough additional information about Europa to make it a high-priority target of investigation in NASA’s search for life.

What makes this moon so alluring is the possibility that it may possess all of the ingredients necessary for life. Scientists have evidence that one of these ingredients, liquid water, is present under the icy surface and may sometimes erupt into space in huge geysers.

But no one has been able to confirm the presence of water in these plumes by directly measuring the water molecule itself. Now, an international research team led out of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre has detected the water vapour for the first time above Europa’s surface.

The team measured the vapour by peering at Europa through one of the world’s biggest telescopes in Hawaii.

Confirming that water vapour is present above Europa helps scientists better understand the inner workings of the moon. For example, it helps support an idea, of which scientists are confident, that there’s a liquid water ocean, possibly twice as big as Earth’s, sloshing beneath this moon’s miles-thick ice shell.

Another source of water for the plumes, some scientists suspect, could be shallow reservoirs of melted water ice not far below Europa’s surface.

It’s also possible that Jupiter’s strong radiation field is stripping water particles from Europa’s ice shell, though the recent investigation argued against this mechanism as the source of the observed water.

“Essential chemical elements (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur) and sources of energy, two of three requirements for life, are found all over the solar system. But the third — liquid water — is somewhat hard to find beyond Earth,” says Lucas Paganini, a NASA planetary scientist who led the water detection investigation. “While scientists have not yet detected liquid water directly, we’ve found the next best thing: water in vapour form.”

Paganini and his team reported in the journal Nature Astronomy on 18 November that they detected enough water releasing from Europa (2360 kg per second) to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool within minutes.

Yet, the scientists also found that the water appears infrequently, at least in amounts large enough to detect from Earth, says Paganini.

“For me, the interesting thing about this work is not only the first direct detection of water above Europa, but also the lack thereof within the limits of our detection method.”

Indeed, Paganini’s team detected the faint yet distinct signal of water vapor just once throughout 17 nights of observations between 2016 and 2017.

Looking at the moon from the WM Keck Observatory atop the dormant Mauna Kea volcano in Hawaii, the scientists saw water molecules at Europa’s leading hemisphere, or the side of the moon that’s always facing in the direction of the moon’s orbit around Jupiter. (Europa, like Earth’s moon, is gravitationally locked to its host planet, so the leading hemisphere always faces the direction of the orbit, while the trailing hemisphere always faces in the opposite direction.)

They used a spectrograph at the Keck Observatory that measures the chemical composition of planetary atmospheres through the infrared light they emit or absorb. Molecules such as water emit specific frequencies of infrared light as they interact with solar radiation.

Before the recent water vapor detection, there have been many tantalizing findings on Europa. The first came from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which measured perturbations in Jupiter’s magnetic field near Europa while orbiting the gas giant planet between 1995 and 2003.

The measurements suggested to scientists that electrically conductive fluid, likely a salty ocean beneath Europa’s ice layer, was causing the magnetic disturbances. When researchers analyzed the magnetic disturbances more closely in 2018, they found evidence of possible plumes.

In the meantime, scientists announced in 2013 that they had used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to detect the chemical elements hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) — components of water (H2O) — in plume-like configurations in Europa’s atmosphere. And, a few years later, other scientists used Hubble to gather more evidence of possible plume eruptions when they snapped photos of finger-like projections that appeared in silhouette as the moon passed in front of Jupiter.

“This first direct identification of water vapor on Europa is a critical confirmation of our original detections of atomic species, and it highlights the apparent sparsity of large plumes on this icy world,” says Lorenz Roth, an astronomer and physicist from KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm who led the 2013 Hubble study and was a co-author of this recent investigation.

Roth’s research, along with other previous Europa findings, have only measured components of water above the surface. The trouble is that detecting water vapor at other worlds is challenging.

Existing spacecraft have limited capabilities to detect it, and scientists using ground-based telescopes to look for water in deep space have to account for the distorting effect of water in Earth’s atmosphere.

To minimise this effect, Paganini’s team used complex mathematical and computer modeling to simulate the conditions of Earth’s atmosphere so they could differentiate Earth’s atmospheric water from Europa’s in data returned by the Keck spectrograph.

“We performed diligent safety checks to remove possible contaminants in ground-based observations,” says Avi Mandell, a Goddard planetary scientist on Paganini’s team. “But, eventually, we’ll have to get closer to Europa to see what’s really going on.”

Scientists will soon be able get close enough to Europa to settle their lingering questions about the inner and outer workings of this possibly habitable world. The forthcoming Europa Clipper mission, expected to launch in the mid-2020s, will round out half a century of scientific discovery that started with a modest photo of a mysterious, veiny eyeball.

When it arrives at Europa, the Clipper orbiter will conduct a detailed survey of Europa’s surface, deep interior, thin atmosphere, subsurface ocean, and potentially even smaller active vents.

Clipper will try to take images of any plumes and sample the molecules it finds in the atmosphere with its mass spectrometers. It will also seek out a fruitful site from which a future Europa lander could collect a sample.

These efforts should further unlock the secrets of Europa and its potential for life.

Other Goddard researchers on Paganini’s team included Geronimo Villanueva, Michael Mumma, and Terry Hurford. Kurt Retherford, from Southwest Research Institute, also contributed to the research.

Main picture: On the left is a view of Europa taken from 2,9-million km away on 2 March 1979 by the Voyager 1 spacecraft. Next is a color image of Europa taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft during its close encounter on 9 July 1979. On the right is a view of Europa made from images taken by the Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s.

Credits: NASA/JPL