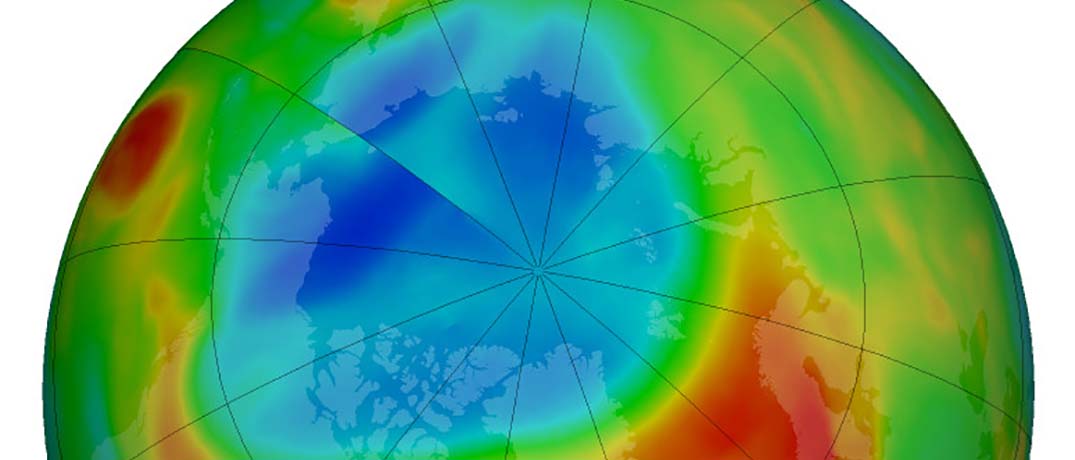

Ozone levels above the Arctic reached a record low for March, NASA researchers report. An analysis of satellite observations show that ozone levels reached their lowest point on 12 March, at 205 Dobson units.

While such low levels are rare, they are not unprecedented. Similar low ozone levels occurred in the upper atmosphere, or stratosphere, in 1997 and 2011. In comparison, the lowest March ozone value observed in the Arctic is usually around 240 Dobson units.

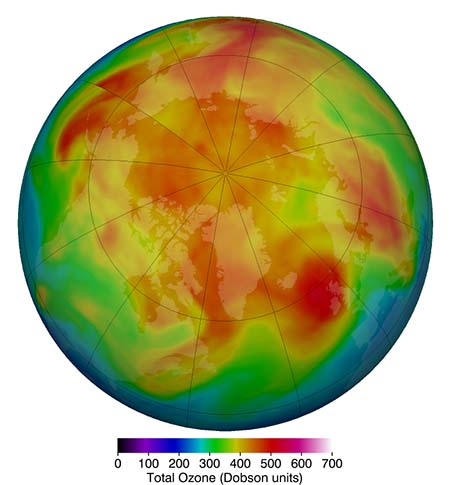

March 12, 2019, shows in reds and yellows the higher concentration of stratospheric ozone over the Arctic which are much more typical from year to year. Usually, from December through March, waves in the upper atmosphere disrupt the circumpolar winds and cause the mixing of ozone brought from the mid-latitudes as well as warming that leads to less ozone depletion.

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

“This year’s low Arctic ozone happens about once per decade,” says Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “For the overall health of the ozone layer, this is concerning since Arctic ozone levels are typically high during March and April.”

Ozone is a highly reactive molecule comprised of three oxygen atoms that occurs naturally in small amounts. The stratospheric ozone layer, roughly 7 to 25 miles above Earth’s surface, is a sunscreen, absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation that can damage plants and animals and affecting people by causing cataracts, skin cancer and suppressed immune systems.

The March Arctic ozone depletion was caused by a combination of factors that arose due to unusually weak upper atmospheric “wave” events from December through March. These waves drive movements of air through the upper atmosphere akin to weather systems that we experience in the lower atmosphere, but much bigger in scale.

In a typical year, these waves travel upward from the mid-latitude lower atmosphere to disrupt the circumpolar winds that swirl around the Arctic. When they disrupt the polar winds, they do two things. First, they bring with them ozone from other parts of the stratosphere, replenishing the reservoir over the Arctic.

“Think of it like having a red-paint dollop, low ozone over the North Pole, in a white bucket of paint,” Newman says. “The waves stir the white paint, higher amounts of ozone in the mid-latitudes, with the red paint or low ozone contained by the strong jet stream circling around the pole.”

The mixing has a second effect, which is to warm the Arctic air. The warmer temperatures then make conditions unfavorable for the formation of polar stratospheric clouds. These clouds enable the release of chlorine for ozone-depleting reactions. Ozone depleting chlorine and bromine come from chlorofluorocarbons and halons, the chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine derived from man-made compounds that are now banned by the Montreal Protocol. The mixing shuts down this chlorine and bromine driven ozone depletion.

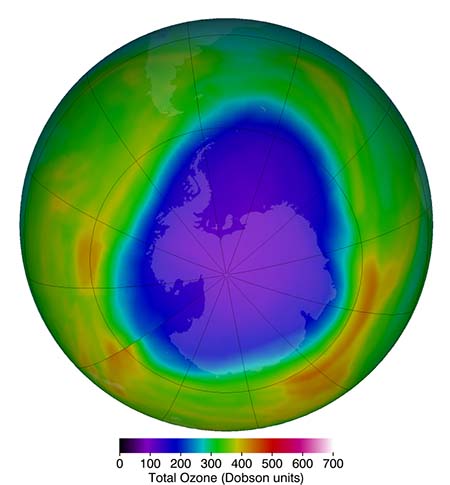

The Antarctic ozone hole that occurs annually in September and October during the Southern Hemisphere spring typically sees much lower ozone levels in than the Arctic. The purples and deep blues show the extent of low ozone levels on October 12, 2018, when they dropped to 104 Dobson units.

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

In December 2019 and January through March of 2020, the stratospheric wave events were weak and did not disrupt the polar winds. The winds thus acted like a barrier, preventing ozone from other parts of the atmosphere from replenishing the low ozone levels over the Arctic. In addition, the stratosphere remained cold, leading to the formation of polar stratospheric clouds which allowed chemical reactions to release reactive forms of chlorine and cause ozone depletion.

“We don’t know what caused the wave dynamics to be weak this year,” Newman says. “But we do know that if we hadn’t stopped putting chlorofluorocarbons into the atmosphere because of the Montreal Protocol, the Arctic depletion this year would have been much worse.”

Since 2000, levels of chlorofluorocarbons and other man-made ozone-depleting substances have measurably decreased in the atmosphere and continue to do so. Chlorofluorocarbons are long-lived compounds that take decades to break down, and scientists expect stratospheric ozone levels to recover to 1980 levels by mid-century.

NASA researchers prefer the term “depletion” over the Arctic, since despite the ozone layer’s record low this year, the ozone loss is still much less than the annual ozone “hole” that occurs over Antarctica in September and October during Southern Hemisphere spring. For comparison, ozone levels over Antarctica typically drop to about 120 Dobson units.

NASA, along with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, monitors stratospheric ozone using satellites, including NASA’s Aura satellite, the NASA-NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite and NOAA’s Joint Polar Satellite System NOAA-20. The Microwave Limb Sounder aboard the Aura satellite also estimates stratospheric levels of ozone-destroying chlorine.

Main picture: Arctic stratospheric ozone reached its record low level of 205 Dobson units, shown in blue and turquoise, on March 12, 2020.

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center