An ongoing, multi-centre clinical trial involving a leading US hospital, Cleveland Clinic, has found that a new blood test can accurately detect more than 50 types of cancer while still in the early stages – before any clinical signs or symptoms of the disease.

According to the results published recently in the Annals of Oncology, in cases where the test detected cancer, it determined where it was located in the body with 93% accuracy. The test has a 0,7% false positive rate, meaning that less than 1% of people would be wrongly identified as having cancer.

“Detecting cancer early is key because it’s easier to treat and increases chances of survival,” says Dr Eric Klein, chairman of Cleveland Clinic’s Glickman Urological & Kidney Institute, a senior author of the Annals of Oncology paper and the co-principal investigator of Cleveland Clinic’s portion of the study along with Taussig Cancer Institute oncologist and vice-chair for research Dr Mikkael Sekeres.

“The hope, ultimately, is to have a validated test that’s highly accurate in terms of detecting the presence of these cancers and a very low false positive rate that can be used for patients at risk for cancer, and have it be part of routine medical practice,” says Dr Klein.

Dr Sekeres adds: “The findings from this study may also have a huge impact on how we monitor patients who have an established cancer diagnosis – with a simple blood test, instead of the need for multiple scans – and have implications for screening patients for cancer across the entire population.”

The screening test’s sensitivity – or its true-positive rate – was 67,3% for stages I-III of 12 of the most common and deadly cancers – anus, bladder, colon/rectum, oesophagus, head and neck, liver/bile duct, lung, lymphoma, ovary, pancreas, stomach and plasma cell neoplasm. The test’s sensitivity increased with higher-stage malignancies.

The test – which is not yet available for clinical use – is being evaluated in a multi-site, three-phase case-control observational clinical trial known as the Circulating Cell-free Genome Atlas (CCGA).

Cleveland Clinic is one of the CCGA’s 142 study locations and enrolled more than 1 500 patients – the largest number of patients of any site. The CCGA study includes more than 15 000 participants from all across North America, ensuring results are generalisable to a diverse population.

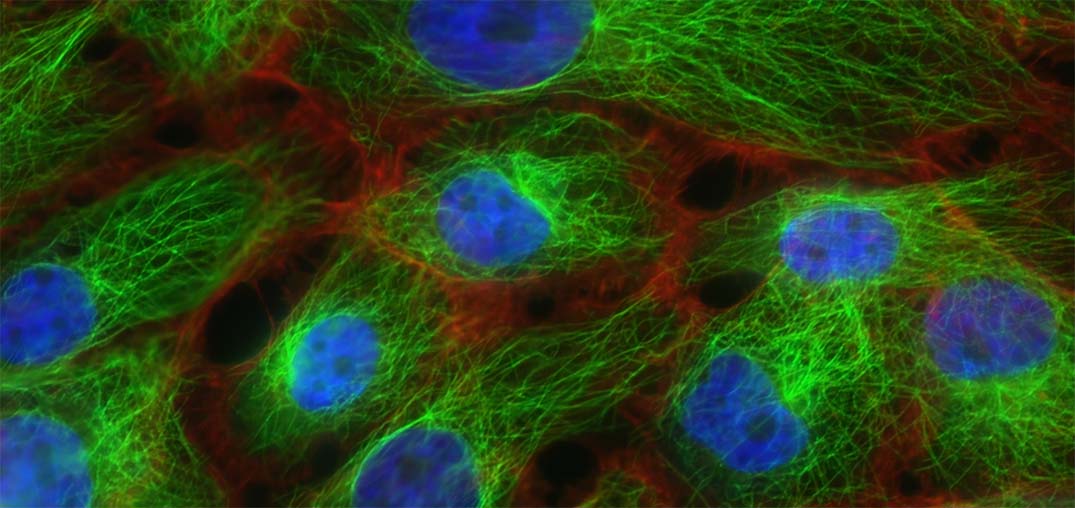

The test works by identifying DNA that cancerous tumors shed into the blood, which contributes to what is known as cell-free DNA (cfDNA). The blood test reported in this study analyses chemical changes to the DNA called “methylation” that usually control gene expression. Abnormal methylation patterns and the resulting changes in gene expression can contribute to tumour growth, so these signals in cfDNA have the potential to detect and localise cancer.

In the part of the CCGA study reported recently, blood samples from 6 689 participants – 2 482 with previously untreated cancer and 4 207 without cancer – from North America were divided into a training set and a validation set. Over 50 types of cancer were included. The machine learning classifier analysed blood samples from the participants to identify methylation changes and to classify the samples as cancer or non-cancer, and to identify the tissue of origin.