Astronomy’s newest mystery objects, odd radio circles or ORCs, have been pulled into sharp focus by an international team of astronomers, including the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Dr Jordan Collier, using the world’s most capable radio telescopes.

First revealed by the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope, owned and operated by Australia’s national science agency the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), odd radio circles quickly became objects of fascination. Theories on what caused them ranged from galactic shockwaves to the throats of wormholes.

A new detailed image, captured by the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory’s (SARAO) MeerKAT radio telescope and published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, is providing researchers with more information to help narrow down those theories.

There are now three leading theories to explain what causes ORCs:

* They could be the remnant of a huge explosion at the centre of their host galaxy, like the merger of two supermassive black holes;

* They could be powerful jets of energetic particles spewing out of the galaxy’s centre; or

* They might be the result of a starburst “termination shock” from the production of stars in the galaxy.

To date ORCs have only been detected using radio telescopes, with no signs of them when researchers have looked for them using optical, infrared, or X-ray telescopes.

Collier who is also part of the Inter-University Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy, compiled the image from MeerKAT data.

“Continuing to observe these odd radio circles will provide researchers with more clues,” he says. “People often want to explain their observations and show that it aligns with our best knowledge. To me, it’s much more exciting to discover something new, that defies our current understanding.”

The rings are enormous – about 1-million light years across, which is 16-times bigger than our own galaxy. Despite this, odd radio circles are hard to see.

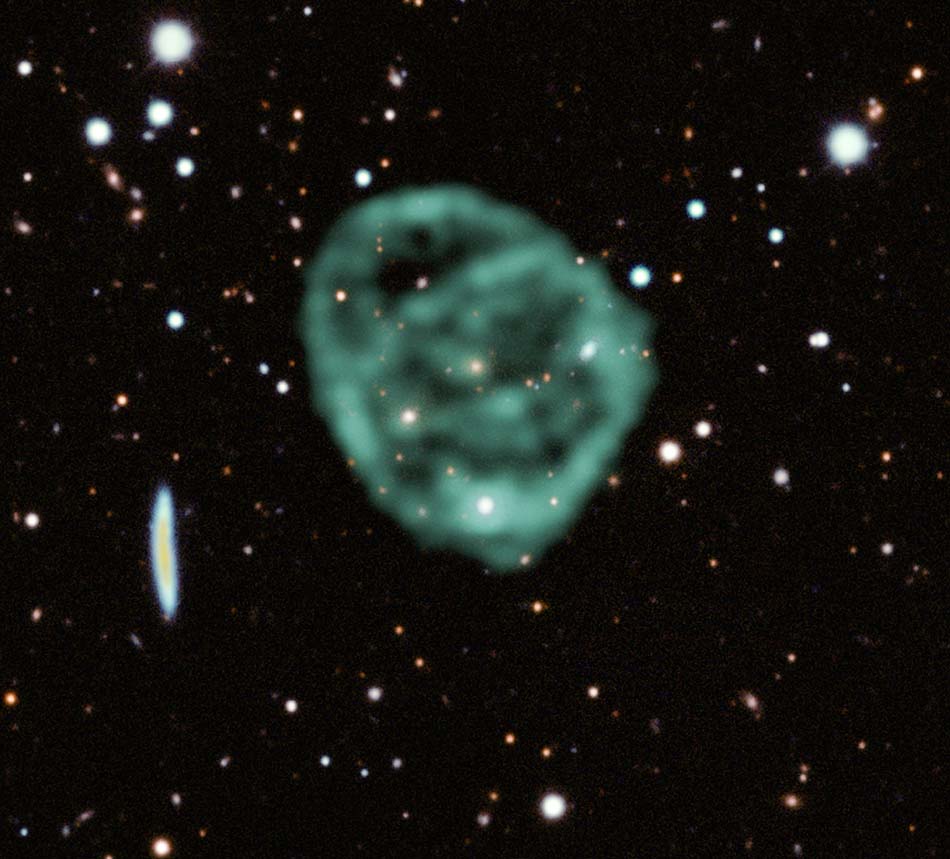

MeerKAT radio telescope data (green), showing the odd radio circles is overlaid on optical and near infra-red data from the Dark Energy Survey.

Credit: J English (U Manitoba)/EMU/MeerKAT/DES/DOE/FNAL/DECam/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

Professor Bärbel Koribalski of the CSIRO, who discovered an odd radio circle in 2021, comments: “Research into odd radio circles makes for exciting discussions, as it involves reaching out to colleagues around the world with expertise in many different areas.

“My team is very diverse and includes everyone from students to senior researchers, working in observing, data processing, modelling or visualisations.”

Professor Ray Norris from Western Sydney University and CSIRO and one of the authors on the paper, says: “Only five odd radio circles have ever been revealed in space.

“We know ORCs are rings of faint radio emissions surrounding a galaxy with a highly active black hole at its centre, but we don’t yet know what causes them, or why they are so rare.”

Dr Fernando Camilo, chief scientist of the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory, which built and operates MeerKAT, explains: “The ORC project is a great example of the clever use of MeerKAT by its users, playing to its strengths: ASKAP observes large swaths of the sky and can discover relatively rare types of objects; MeerKAT can then follow up to study them in greater detail.”

To really understand odd radio circles scientists will need access to even more sensitive radio telescopes such as those of the SKA Observatory, which is supported by more than a dozen countries including South Africa, Australia, the UK, France, Canada, China and India.

Professor Elaine Sadler, chief scientist of CSIRO’s Australia Telescope National Facility, which includes ASKAP, says that, for now, ASKAP and MeerKAT are working together to find and describe these objects quickly and efficiently.

“Nearly all astronomy projects are made better by international collaboration – both with the teams of people involved and the technology available,” she says.

Norris adds: “No doubt the SKA telescopes, once built, will find many more ORCs and be able to tell us more about the lifecycle of galaxies. Until the SKA becomes operational, ASKAP and MeerKAT are set to revolutionise our understanding of the Universe faster than ever before.”

Artist’s impression of odd radio circles exploding from a central galaxy. It is thought to take the rings 1-billion years to reach the size we see them today. The rings are so big (millions of light years across), they’ve expanded past other galaxies. Credit: Sam Moorfield/CSIRO

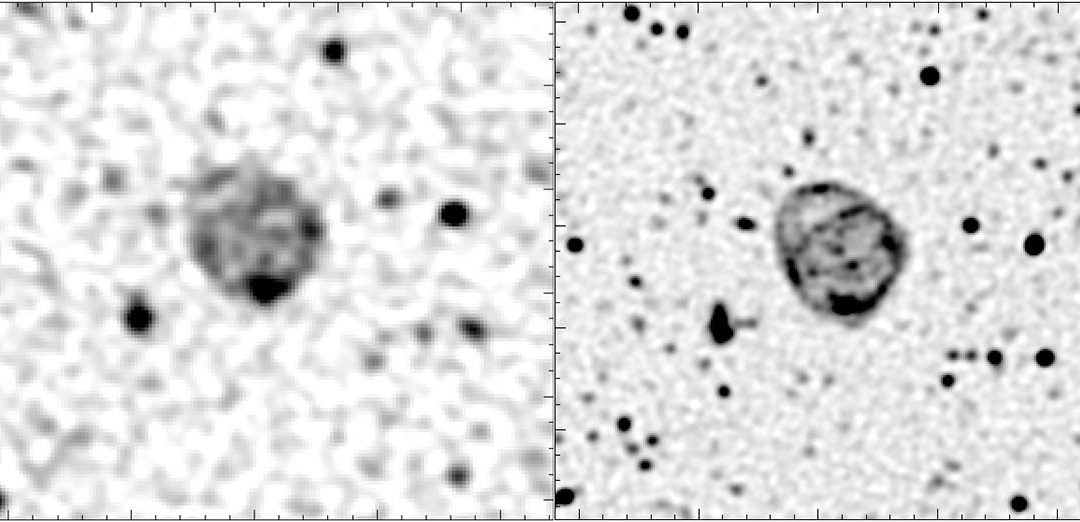

Featured picture: The original discovery of the ORCs in the EMU survey’s ASKAP data is on the left; the follow-up observation of the ORCs with MeerKAT is on the right.

Credit: EMU/ASKAP/MeerKAT