At 6:28am EDT on 21 August 1972, NASA’s Copernicus satellite, the heaviest and most complex space telescope of its time, lit up the sky as it ascended into orbit from Launch Complex 36B at what is now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida.

Initially known as Orbiting Astronomical Observatory (OAO) C, it became OAO 3 once in orbit in the fashion of the time. But it was also renamed to honor the 500th anniversary of the birth of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543). The Polish astronomer formulated a model of the solar system with the Sun in the central position instead of Earth, breaking with 1 300 years of tradition and triggering a scientific revolution.

Fitted with the largest ultraviolet telescope ever orbited at the time as well as four co-aligned X-ray instruments, Copernicus was arguably NASA’s first dedicated multiwavelength astronomy observatory. This makes it a forebear of operating satellites like NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, which watches the sky in visible, ultraviolet, and X-ray light.

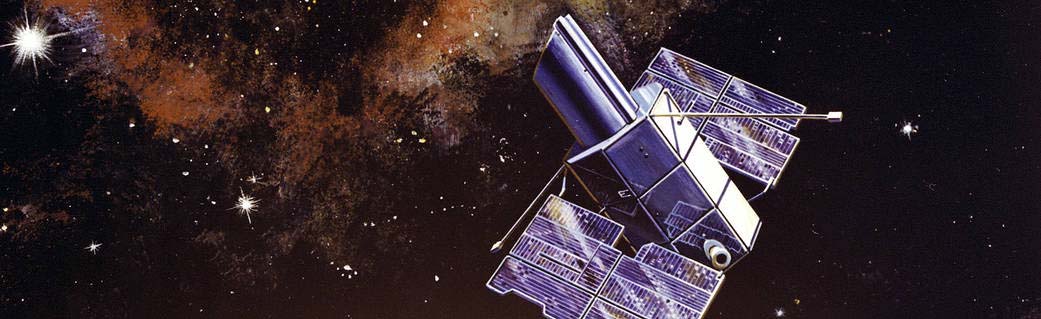

Orbiting Astronomical Observatory C – named Copernicus in orbit – stands in the Hangar AE clean room at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, following the mounting of its stationary solar panels. Copernicus was the only member of the series sporting the large cylindrical structures at the top of the spacecraft, which kept stray light from reaching the instruments.

Credit: NASA

“The two spacecraft share institutional connections, too,” notes Swift Principal Investigator S Bradley Cenko at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre. “Goddard managed both missions, and the X-ray experiment on Copernicus was provided by the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London, which also contributed Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope.”

Learning to point and hold an orbiting telescope on a star long enough for the detectors to capture its light proved much more difficult than expected. Satellites designed to study the Sun at the time had a built-in advantage – they targeted the solar system’s brightest object. Copernicus flew with a new inertial reference unit (IRU) developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Gyroscopes in the IRU sped up the process of acquiring targets, while other systems kept the satellite locked on. In a study of the mission’s first 500 days, one engineer summed it up by noting that the IRU had made flying Copernicus “a boring operation.”

In NASA’s early days, astronomers emphasized the need for ultraviolet (UV) studies, which could not be made from the ground, and this became the primary focus of the OAO program. Of four satellites launched, one failed after three days in space, and another never reached orbit at all. OAO 2, launched in 1968 and named Stargazer, provided years of observations, including low-resolution stellar spectra, which spread out wavelengths much like a rainbow to reveal the UV fingerprints of specific molecules and atoms. Copernicus went deeper still, capturing spectra with up to 200 times better detail in some wavelengths.

“This mission obtained high-resolution spectra of many stars in the UV and provided information at the shortest wavelengths reached for many years,” wrote Nancy Grace Roman, the first chief of astronomy in the Office of Space Science at NASA Headquarters, and the program scientist for Copernicus.

During the mission, Roman became one of the driving forces behind the Large Space Telescope project, now known as NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. She is also the namesake of NASA’s Roman Space Telescope, which is expected to take flight in a few years.

The hot, young star Zeta Ophiuchi is seen here in infrared (green and red) and X-ray light (blue) from NASA’s Spitzer and Chandra space telescopes. The star is partly veiled by an interstellar cloud. Its stellar outflows and motion through space combine to produce the red and green shock wave. Copernicus measured the star’s ultraviolet light, finding evidence that most interstellar gas comes in the form of molecular hydrogen.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Dublin Inst. Advanced Studies/S. Green et al.; Infrared: NASA/JPL/Spitzer

The primary instrument aboard Copernicus was the Princeton Experiment Package, which captured UV light using a 0,8-metre mirror about a third the size of Hubble’s. Led by Lyman Spitzer Jr. at Princeton University in New Jersey, the instrument produced a treasure trove of information about interstellar gas and the ionised outflows of hot stars.

Its first target, a star named Zeta Ophiuchi that’s partly veiled by an interstellar cloud, showed strong absorption from hydrogen molecules. Measurements from dozens of other stars confirmed a theory predicting that most of the hydrogen in gas clouds existed in this form.

In 1946, Spitzer began speculating about the kinds of science that might be possible with a large orbiting telescope, later becoming the catalyst for the development of Hubble. NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, which operated from 2003 to 2020 and explored, among other sources, the cold clouds where stars are born, was named in his honor.

At the time when NASA was considering instrument proposals for Copernicus, only one celestial object, the Sun, was known to emit X-rays. That changed in 1962. Flying new X-ray detectors on a suborbital rocket, a research team led by Riccardo Giacconi at American Science and Engineering Inc., then in Cambridge, Massachusetts, discovered the first X-ray source beyond the solar system, named Scorpius X-1. Additional flights uncovered more cosmic sources, including Cygnus X-1, long suspected and now known to host a stellar-mass black hole.

With this breakthrough, Giaconni proposed the first satellite dedicated to mapping the X-ray sky. Launched in 1970 and operating for three years, NASA’s Uhuru satellite mapped more than 300 sources, showed that many are neutron stars or black holes fueled by gas streaming from stellar companions, and discovered X-rays from the hot gas in galaxy clusters. Giaconni would go on to propose more powerful X-ray satellites – NASA’s Einstein Observatory, which operated from 1978 to 1981, and NASA’s current X-ray flagship, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, launched in 1999.

This mid-1960s illustration shows an astronaut servicing a future OAO satellite. Astronauts made orbital repairs to Skylab, NASA’s first space station, in 1973 and to the Solar Maximum Mission satellite in 1984. But the vision illustrated here found its ultimate realization with the five successful missions to service and upgrade NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope from 1993 to 2009.

Credit: NASA

The X-ray experiment aboard Copernicus was led by Robert Boyd at University College London, and the three telescopes experienced significant challenges. Longer-wavelength detectors were swamped by an unexpectedly high level of background radiation. It proved to come from a vast comet-shaped cloud of hydrogen atoms surrounding Earth, called the geocorona, that scatters far-ultraviolet sunlight. Later instruments added a filter tuned to absorb the UV but let X-rays pass through.

In June 1973, scientists at Goddard noticed a problem with a shutter in the X-ray telescopes. The device was used to periodically block X-rays from reaching the detector so scientists could track the changing background radiation from charged particles in different parts of the orbit. Now its operation had become hesitant. Concerned that the shutter might remain permanently in the closed position, the instrument team had decided to stop using it. But a final command made it through – and the sticky shutter stuck closed, blinding the instruments.

A fourth detector unattached to a telescope continued working for the duration of the mission. This X-ray counter measured radiation from 1 to 3 angstroms over a wide field of view – 2.5 by 3.5 degrees, about 40 times the apparent area of a full Moon.

The X-ray experiment discovered several long-period pulsars, including X Persei. Pulsars – typically, spinning neutron stars – swing a beam of radiation in our direction each time they rotate, usually at tens to thousands of times a second. Oddly, the X Persei pulsar takes a leisurely 14 minutes per spin.

Copernicus performed long-term monitoring of pulsars and other bright sources, and it observed Nova Cygni 1975, an explosion on the white dwarf in a close binary system. The experiment discovered curious dips in X-ray absorption at Cygnus X-1, likely caused by cool, dense clumps in the gas flowing away from the star. And the satellite recorded varying X-rays from the black-hole-powered galaxy Centaurus A, located about 12-million light-years away.

Copernicus returned UV and X-ray observations for 8.5 years before its retirement in 1981, and it still orbits Earth today. It departed space astronomy’s center stage as more advanced observatories appeared, notably Einstein and the International Ultraviolet Explorer, which launched in 1978 and operated for nearly 19 years. Copernicus observations appear in more than 650 scientific papers. Its instruments studied some 450 unique objects targeted by more than 160 investigators in the United States and 13 other countries.