The annual Antarctic ozone hole reached an average area of 23,2-million square kilometres between 7 September and 13 October 2022. This depleted area of the ozone layer over the South Pole was slightly smaller than last year and generally continued the overall shrinking trend of recent years.

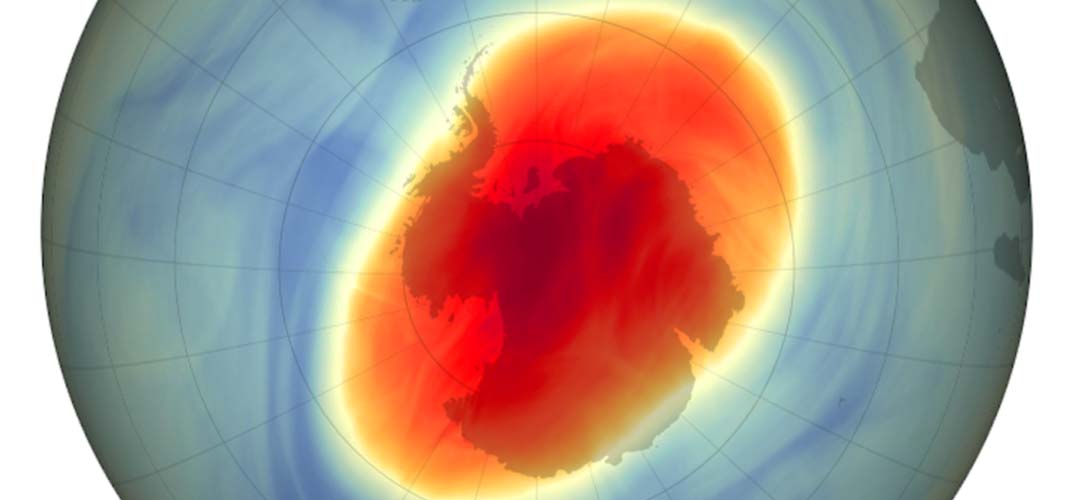

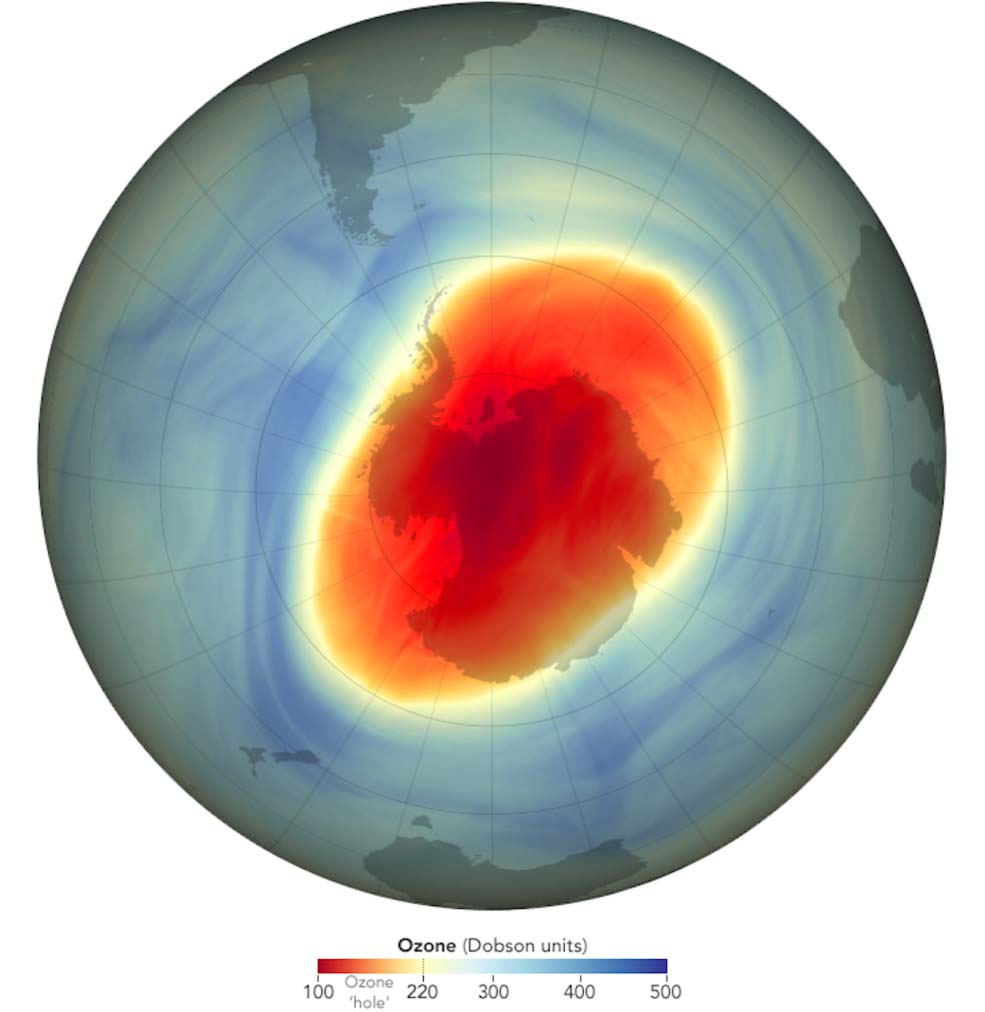

This map shows the size and shape of the ozone hole over the South Pole on 5 October 2022, when it reached its single-day maximum extent for the year.

Credits: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens

“Over time, steady progress is being made, and the hole is getting smaller,” said Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre. “We see some wavering as weather changes and other factors make the numbers wiggle slightly from day to day and week to week. But overall, we see it decreasing through the past two decades. The elimination of ozone-depleting substances through the Montreal Protocol is shrinking the hole.”

The ozone layer – the portion of the stratosphere that protects our planet from the Sun’s ultraviolet rays – thins to form an “ozone hole” above the South Pole every September. Chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine in the atmosphere, derived from human-produced compounds, attach to high-altitude polar clouds each southern winter. The reactive chlorine and bromine then initiate ozone-destroying reactions as the Sun rises at the end of Antarctica’s winter.

Researchers at NASA and NOAA detect and measure the growth and breakup of the ozone hole with instruments aboard the Aura, Suomi NPP, and NOAA-20 satellites. On 5 October 2022, those satellites observed a single-day maximum ozone hole of 26,4-million square kilometres, slightly larger than last year.

When the polar sun rises, NOAA scientists also make measurements with a Dobson Spectrophotometer, an optical instrument that records the total amount of ozone between the surface and the edge of space – known as the total column ozone value.

Globally, the total column average is about 300 Dobson Units. On 3 October 2022, scientists recorded a lowest total-column ozone value of 101 Dobson Units over the South Pole. At that time, ozone was almost completely absent at altitudes between 14 and 21 kilometers – a pattern very similar to last year.

Some scientists were concerned about potential stratospheric impacts from the January 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano. The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption released substantial amounts of sulfur dioxide that amplified ozone layer depletion. However, no direct impacts from Hunga Tonga have been detected in the Antarctic stratospheric data.