Like a sports photographer at an auto-racing event, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope captured a series of photos of asteroid Dimorphos when it was deliberately hit by a 1 200-pound NASA spacecraft called DART on 26 September 2022.

The primary objective of DART, which stands for Double Asteroid Redirection Test, was to test our ability to alter the asteroid’s trajectory as it orbits its larger companion asteroid, Didymos. Though neither Didymos nor Dimorphos poses any threat to Earth, data from the mission will help inform researchers how to potentially divert an asteroid’s path away from Earth, if ever necessary. The DART experiment also provided fresh insights into planetary collisions that may have been common in the early solar system.

Hubble’s time-lapse movie of the aftermath of DART’s collision reveals surprising and remarkable, hour-by-hour changes as dust and chunks of debris were flung into space. Smashing head on into the asteroid at 13 000 miles per hour, the DART impactor blasted over 1 000 tons of dust and rock off of the asteroid.

The Hubble movie offers invaluable new clues into how the debris was dispersed into a complex pattern in the days following the impact. This was over a volume of space much larger than could be recorded by the LICIACube cubesat, which flew past the binary asteroid minutes after DART’s impact.

This movie captures the breakup of the asteroid Dimorphos when it was deliberately hit by NASA’s 1,200-pound Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission spacecraft on September 26, 2022. The Hubble Space Telescope had a ringside view of the space demolition derby. The Hubble movie starts at 1.3 hours before impact. The first post-impact snapshot is 2 hours after the event. Debris flies away from the asteroid in straight lines, moving faster than four miles per hour (fast enough to escape the asteroid’s gravitation pull, so it does not fall back onto the asteroid). The ejecta forms a largely hollow cone with long, stringy filaments. At about 17 hours after the impact the debris pattern entered a second stage. The dynamic interaction within the binary system started to distort the cone shape of the ejecta pattern. The most prominent structures are rotating, pinwheel-shaped features. The pinwheel is tied to the gravitational pull of the companion asteroid, Didymos. Hubble next captures the debris being swept back into a comet-like tail by the pressure of sunlight on the tiny dust particles. This stretches out into a debris train where the lightest particles travel the fastest and farthest from the asteroid. The mystery is compounded later when Hubble records the tail splitting in two for a few days.

Credits: NASA, ESA, STScI, and Jian-Yang Li (PSI); Video: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

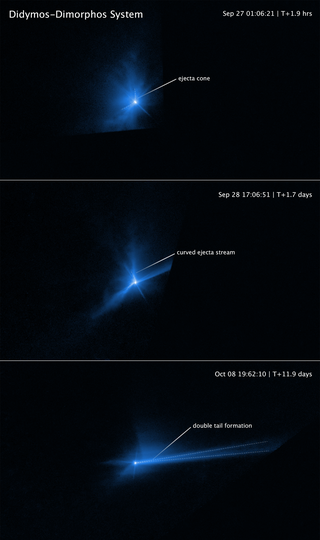

These three Hubble images capture the breakup of the asteroid Dimorphos when it was deliberately hit by NASA’s 1,200-pound Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission spacecraft on September 26, 2022. The top panel, taken 2 hours after impact, shows an ejecta cone (an estimated 1,000 tons of dust). The center frame shows the dynamic interaction within the asteroid’s binary system that starts to distort the cone shape of the ejecta pattern about 17 hours after the impact. The most prominent structures are rotating, pinwheel-shaped features. The pinwheel is tied to the gravitational pull of the companion asteroid, Didymos. In the bottom frame, Hubble captures debris being swept back into a comet-like tail by the pressure of sunlight on the tiny dust particles. This stretches out into a debris train where the lightest particles travel the fastest and farthest from the asteroid. The mystery is compounded when Hubble records the tail splitting in two for a few days.

Credits: NASA, ESA, STScI, and Jian-Yang Li (PSI); Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

“The DART impact happened in a binary asteroid system. We’ve never witnessed an object collide with an asteroid in a binary asteroid system before in real time, and it’s really surprising. I think it’s fantastic. Too much stuff is going on here. It’s going to take some time to figure out,” says Jian-Yang Li of the Planetary Science Institute. The study, led by Li along with 63 other DART team members, was published on 1 March in the journal Nature.

The movie shows three overlapping stages of the impact aftermath: the formation of an ejecta cone, the spiral swirl of debris caught up along the asteroid’s orbit about its companion asteroid, and the tail swept behind the asteroid by the pressure of sunlight (resembling a windsock caught in a breeze).

The Hubble movie starts at 1,3 hours before impact. In this view both Didymos and Dimorphos are within the central bright spot; even Hubble can’t resolve the two asteroids separately. The thin, straight spikes projecting away from the center (and seen in later images) are artifacts of Hubble’s optics. The first post-impact snapshot is two hours after the event. Debris flies away from the asteroid, moving with a range of speeds faster than four miles per hour (fast enough to escape the asteroid’s gravitational pull, so it does not fall back onto the asteroid). The ejecta forms a largely hollow cone with long, stringy filaments.

At about 17 hours after the impact the debris pattern entered a second stage. The dynamic interaction within the binary system starts to distort the cone shape of the ejecta pattern. The most prominent structures are rotating, pinwheel-shaped features. The pinwheel is tied to the gravitational pull of the companion asteroid, Didymos. “This is really unique for this particular incident,” says Li. “When I first saw these images, I couldn’t believe these features. I thought maybe the image was smeared or something.”

Hubble next captures the debris being swept back into a comet-like tail by the pressure of sunlight on the tiny dust particles. This stretches out into a debris train where the lightest particles travel the fastest and farthest from the asteroid. The mystery is compounded later when Hubble records the tail splitting in two for a few days.

A multitude of other telescopes on Earth and in space, including NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and Lucy spacecraft, also observed the DART impact and its outcomes.