On Sunday 9 October 2022, a pulse of intense radiation swept through the solar system so exceptional that astronomers quickly dubbed it the BOAT – the brightest of all time.

The source was a gamma-ray burst (GRB), the most powerful class of explosions in the universe.

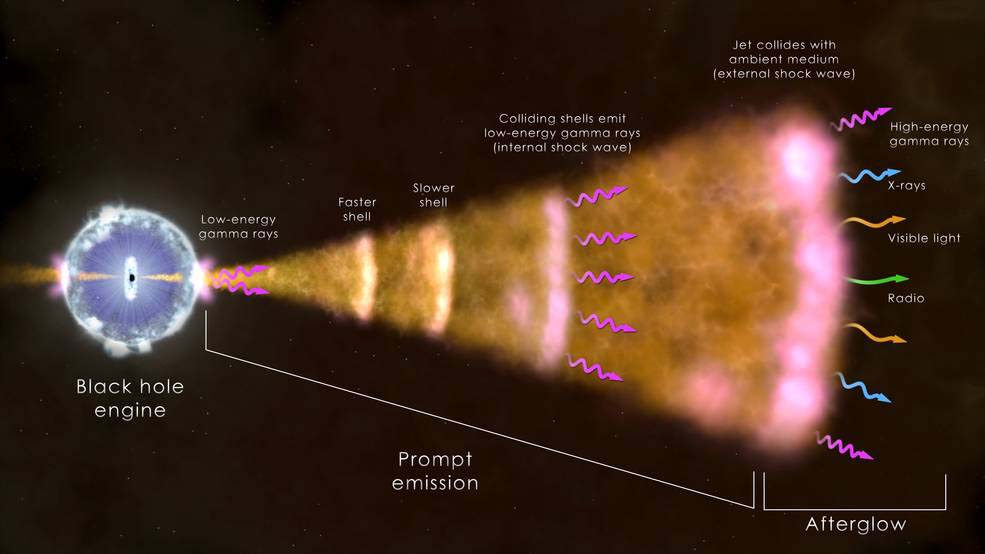

Gamma-ray bursts are the most luminous explosions in the cosmos. Astronomers think most occur when the core of a massive star runs out of nuclear fuel, collapses under its own weight, and forms a black hole, as illustrated in this animation. The black hole then drives jets of particles that drill all the way through the collapsing star at nearly the speed of light. These jets pierce through the star, emitting X-rays and gamma rays (magenta) as they stream into space. They then plow into material surrounding the doomed star and produce a multiwavelength afterglow that gradually fades away. The closer to head-on we view one of these jets, the brighter it appears.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

The burst triggered detectors on numerous spacecraft, and observatories around the globe followed up. After combing through all of this data, astronomers can now characterize just how bright it was and better understand its scientific impact.

“GRB 221009A was likely the brightest burst at X-ray and gamma-ray energies to occur since human civilization began,” said Eric Burns, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. He led an analysis of some 7,000 GRBs – mostly detected by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and the Russian Konus instrument on NASA’s Wind spacecraft – to establish how frequently events this bright may occur. Their answer: once in every 10,000 years.

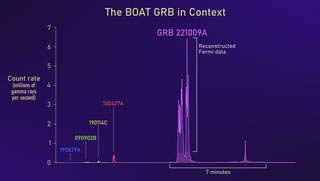

This chart compares the BOAT’s prompt emission to that of five previous record-holding long gamma-ray bursts. The BOAT was so bright it effectively blinded most gamma-ray instruments in space, but U.S. scientists were able to reconstruct its true brightness from Fermi data.

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and Adam Goldstein (USRA)

The burst was so bright it effectively blinded most gamma-ray instruments in space, which means they could not directly record the real intensity of the emission. U.S. scientists were able to reconstruct this information from the Fermi data. They then compared the results with those from the Russian team working on Konus data and Chinese teams analyzing observations from the GECAM-C detector on their SATech-01 satellite and instruments on their Insight-HXMT observatory. Together, they prove the burst was 70 times brighter than any yet seen.

Burns and other scientists presented new findings about the BOAT at the High Energy Astrophysics Division meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Waikoloa, Hawaii. Observations of the burst span the spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays, and include data from many NASA and partner missions, including the NICER X-ray telescope on the International Space Station, NASA’s NuSTAR observatory, and even Voyager 1 in interstellar space. Papers describing the results presented appear in a focus issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The signal from GRB 221009A had been traveling for about 1.9 billion years before it reached Earth, making it among the closest-known “long” GRBs, whose initial, or prompt, emission lasts more than two seconds. Astronomers think these bursts represent the birth cries of black holes formed when the cores of massive stars collapse under their own weight. As it quickly ingests the surrounding matter, the black hole blasts out jets in opposite directions containing particles accelerated to near the speed of light. These jets pierce through the star, emitting X-rays and gamma rays as they stream into space.

With this type of GRB, astronomers expect to find a brightening supernova a few weeks later, but so far it has proven elusive. One reason is that the GRB appeared in a part of the sky that’s just a few degrees above the plane of our own galaxy, where thick dust clouds can greatly dim incoming light.

“We cannot say conclusively that there is a supernova, which is surprising given the burst’s brightness,” said Andrew Levan, a professor of astrophysics at Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands. Since dust clouds become more transparent at infrared wavelengths, Levan led near- and mid-infrared observations using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope – its first use for this kind of study – as well as the Hubble Space Telescope to spot the supernova. “If it’s there, it’s very faint. We plan to keep looking,” he added, “but it’s possible the entire star collapsed straight into the black hole instead of exploding.” Additional Webb and Hubble observations are planned over the next few months.

As the jets continue to expand into material surrounding the doomed star, they produce a multiwavelength afterglow that gradually fades away.

This illustration shows the ingredients of a long gamma-ray burst, the most common type. The core of a massive star (left) has collapsed, forming a black hole that sends a jet of particles moving through the collapsing star and out into space at nearly the speed of light. Radiation across the spectrum arises from hot ionized gas (plasma) in the vicinity of the newborn black hole, collisions among shells of fast-moving gas within the jet (internal shock waves), and from the leading edge of the jet as it sweeps up and interacts with its surroundings (external shock).

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

“Being so close and so bright, this burst offered us an unprecedented opportunity to gather observations of the afterglow across the electromagnetic spectrum and to test how well our models reflect what’s really happening in GRB jets,” said Kate Alexander, an assistant professor in the department of astronomy at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “Twenty-five years of afterglow models that have worked very well cannot completely explain this jet,” she said. “In particular, we found a new radio component we don’t fully understand. This may indicate additional structure within the jet or suggest the need to revise our models of how GRB jets interact with their surroundings.”

The jets themselves were not unusually powerful, but they were exceptionally narrow – much like the jet setting of a garden hose – and one was pointed directly at us, Alexander explained. The closer to head-on we view a jet, the brighter it appears. Although the afterglow was unexpectedly dim at radio energies, it’s likely that GRB 221009A will remain detectable for years, providing a novel opportunity to track the full life cycle of a powerful jet.

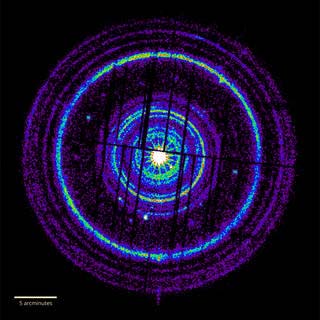

The burst also enabled astronomers to probe distant dust clouds in our own galaxy. As the prompt X-rays traveled toward us, some of them reflected off of dust layers, creating extended “light echoes” of the initial blast in the form of X-ray rings expanding from the burst’s location. The X-ray Telescope on NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory discovered the presence of a series of echoes. Detailed follow-up by ESA’s (the European Space Agency’s) XMM-Newton telescope, together with Swift data, revealed these extraordinary rings were produced by 21 distinct dust clouds.

“How dust clouds scatter X-rays depends on their distances, the sizes of the dust grains, and the X-ray energies,” explained Sergio Campana, research director at Brera Observatory and the National Institute for Astrophysics in Merate, Italy. “We were able to use the rings to reconstruct part of the burst’s prompt X-ray emission and to determine where in our galaxy the dust clouds are located.”

XMM-Newton images recorded 20 dust rings, 19 of which are shown here in arbitrary colors. This composite merges observations made two and five days after GRB 221009A erupted. Dark stripes indicate gaps between the detectors. A detailed analysis shows that the widest ring visible here, comparable to the apparent size of a full moon, came from dust clouds located about 1,300 light-years away. The innermost ring arose from dust at a distance of 61,000 light-years – on the other side of our galaxy. GRB221009A is only the seventh gamma-ray burst to display X-ray rings, and it triples the number previously seen around one.

Credit: ESA/XMM-Newton/M. Rigoselli (INAF)

GRB 221009A is only the seventh gamma-ray burst to display X-ray rings, and it triples the number previously seen around one. The echoes came from dust located between 700 and 61,000 light-years away. The most distant echoes – clear on the other side of our Milky Way galaxy – were also 4,600 light-years above the galaxy’s central plane, where the solar system resides.

Lastly, the burst offers an opportunity to explore a big cosmic question. “We think of black holes as all-consuming things, but do they also return power back to the universe?” asked Michela Negro, an astrophysicist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt.

Her team was able to probe the dust rings with NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer to glimpse how the prompt emission was organized, which can give insights into how the jets form. In addition, a small degree of polarization observed in the afterglow phase confirms that we viewed the jet almost directly head-on.

Together with similar measurements now being studied by a team using data from ESA’s INTEGRAL observatory, scientists say it may be possible to prove that the BOAT’s jets were powered by tapping into the energy of a magnetic field amplified by the black hole’s spin. Predictions based on such models have already successfully explained other aspects of this burst.

Featured image: The Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 revealed the infrared afterglow (circled) of the BOAT GRB and its host galaxy, seen nearly edge-on as a sliver of light extending to the burst’s upper right. This composite incorporates images taken on Nov. 8 and Dec. 4, 2022, one and two months after the eruption. Given its brightness, the burst’s afterglow may remain detectable by telescopes for several years. The picture combines three near-infrared images taken each day at wavelengths from 1 to 1.5 microns.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Levan (Radboud University); Image Processing: Gladys Kober