Kelvin waves, a potential precursor of El Niño conditions in the ocean, are rolling across the equatorial Pacific toward the coast of South America.

The most recent sea level data from the US-European satellite Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich indicates early signs of a developing El Niño across the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

The data shows Kelvin waves – which are roughly 5cm to 10cn high at the ocean surface and hundreds of miles wide – moving from west to east along the equator toward the west coast of South America.

When they form at the equator, Kelvin waves bring warm water, which is associated with higher sea levels, from the western Pacific to the eastern Pacific. A series of Kelvin waves starting in spring is a well-known precursor to an El Niño, a periodic climate phenomenon that can affect weather patterns around the world. It is characterized by higher sea levels and warmer-than-average ocean temperatures along the western coasts of the Americas.

Water expands as it warms, so sea levels tend to be higher in places with warmer water. El Niño is also associated with a weakening of the trade winds. The condition can bring cooler, wetter conditions to the US Southwest and drought to countries in the western Pacific, such as Indonesia and Australia.

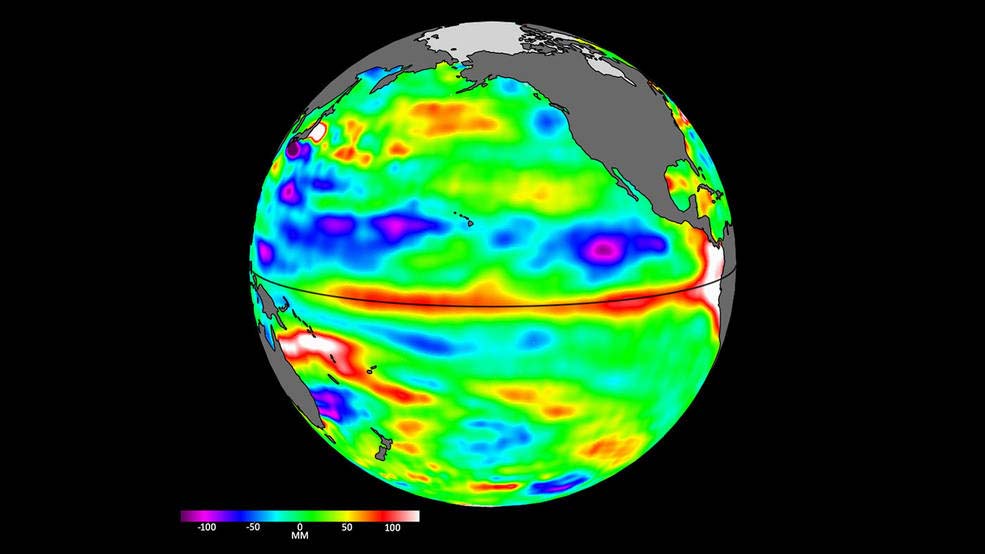

Sea level data from the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite on April 24 shows relatively higher (shown in red and white) and warmer ocean water at the equator and the west coast of South America. Water expands as it warms, so sea levels tend to be higher in places with warmer water.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite data shown here covers the period between the beginning of March and the end of April 2023. By April 24, Kelvin waves had piled up warmer water and higher sea levels (shown in red and white) off the coasts of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Satellites like Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich can detect Kelvin waves with a radar altimeter, which uses microwave signals to measure the height of the ocean’s surface. When an altimeter passes over areas that are warmer than others, the data will show higher sea levels.

“We’ll be watching this El Niño like a hawk,” says Josh Willis, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “If it’s a big one, the globe will see record warming.”

Both the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the World Meteorological Organisation have recently reported increased chances that El Niño will develop by the end of the Northern Hemisphere summer. Continued monitoring of ocean conditions in the Pacific by instruments and satellites such as Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich should help to clarify in the coming months how strong it could become.

“When we measure sea level from space using satellite altimeters, we know not only the shape and height of water, but also its movement, like Kelvin and other waves,” says Nadya Vinogradova Shiffer, NASA program scientist and manager for Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich. “Ocean waves slosh heat around the planet, bringing heat and moisture to our coasts and changing our weather.”

Featured picture: This animation shows a series of waves, called Kelvin waves, moving warm water across the equatorial Pacific Ocean from west to east during March and April. The signals can be an early sign of a developing El Niño, and were detected by the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich sea level satellite.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech