The latest image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope shows a portion of the dense center of our galaxy in unprecedented detail, including never-before-seen features astronomers have yet to explain.

The star-forming region, named Sagittarius C (Sgr C), is about 300 light-years from the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A.

“There’s never been any infrared data on this region with the level of resolution and sensitivity we get with Webb, so we are seeing lots of features here for the first time,” says the observation team’s principal investigator Samuel Crowe, an undergraduate student at the University of Virginia. “Webb reveals an incredible amount of detail, allowing us to study star formation in this sort of environment in a way that wasn’t possible previously.”

“The galactic center is the most extreme environment in our Milky Way galaxy, where current theories of star formation can be put to their most rigorous test,” added professor Jonathan Tan, one of Crowe’s advisors at the University of Virginia.

Protostars

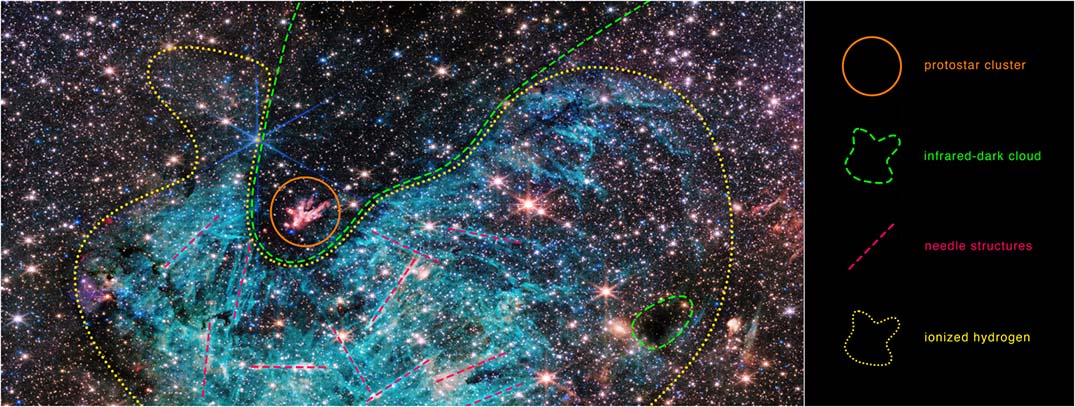

Amid the estimated 500 000 stars in the image is a cluster of protostars – stars that are still forming and gaining mass – producing outflows that glow like a bonfire in the midst of an infrared-dark cloud. At the heart of this young cluster is a previously known, massive protostar over 30-times the mass of our Sun.

The cloud the protostars are emerging from is so dense that the light from stars behind it cannot reach Webb, making it appear less crowded when in fact it is one of the most densely packed areas of the image. Smaller infrared-dark clouds dot the image, looking like holes in the starfield. That’s where future stars are forming.

Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument also captured large-scale emission from ionized hydrogen surrounding the lower side of the dark cloud, shown cyan-colored in the image. Typically, Crowe says, this is the result of energetic photons being emitted by young massive stars, but the vast extent of the region shown by Webb is something of a surprise that bears further investigation.

Another feature of the region that Crowe plans to examine further is the needle-like structures in the ionised hydrogen, which appear oriented chaotically in many directions.

“The galactic center is a crowded, tumultuous place. There are turbulent, magnetized gas clouds that are forming stars, which then impact the surrounding gas with their outflowing winds, jets, and radiation,” says Rubén Fedriani, a co-investigator of the project at the Instituto Astrofísica de Andalucía in Spain. “Webb has provided us with a ton of data on this extreme environment, and we are just starting to dig into it.”

Approximate outlines help to define the features in the Sagittarius C (Sgr C) region. Astronomers are studying data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to understand the relationship between these features, as well as other influences in the chaotic galaxy centre.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Samuel Crowe (UVA)

Around 25 000 light-years from Earth, the galactic center is close enough to study individual stars with the Webb telescope, allowing astronomers to gather unprecedented information on how stars form, and how this process may depend on the cosmic environment, especially compared to other regions of the galaxy. For example, are more massive stars formed in the centre of the Milky Way, as opposed to the edges of its spiral arms?

“The image from Webb is stunning, and the science we will get from it is even better,” Crowe says. “Massive stars are factories that produce heavy elements in their nuclear cores, so understanding them better is like learning the origin story of much of the universe.”

Featured image: The NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s reveals a portion of the Milky Way’s dense core in a new light. An estimated 500 000 stars shine in this image of the Sagittarius C (Sgr C) region, along with some as-yet unidentified features. A large region of ionised hydrogen, shown in cyan, contains intriguing needle-like structures that lack any uniform orientation.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, and S Crowe (University of Virginia).