Microsoft may have changed the quantum computing game, with the development of a new material that enables scalability on a new scale.

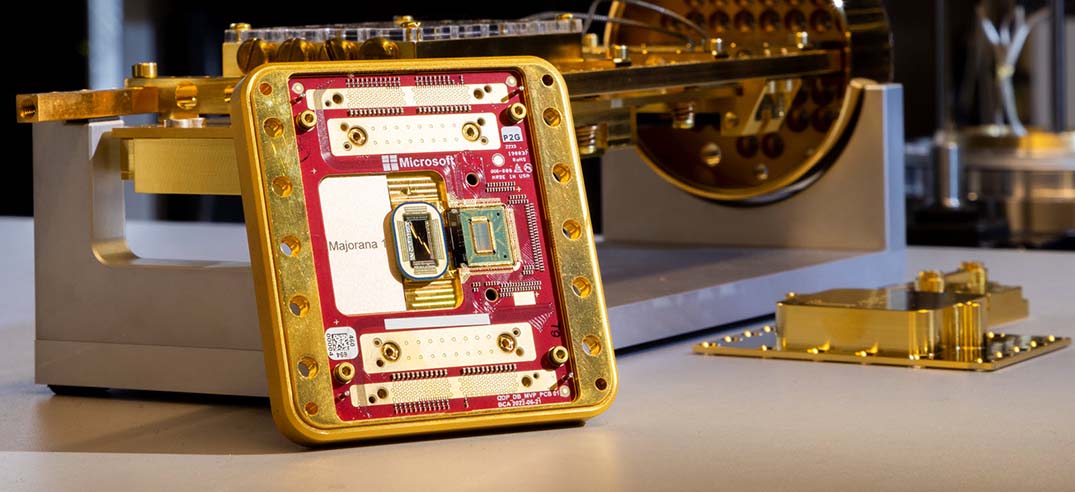

Majorana 1, introduced yesterday, is the world’s first quantum chip powered by a new Topological Core architecture that Microsoft expects to realize quantum computers capable of solving meaningful, industrial-scale problems in years rather than decades.

It leverages the world’s first topoconductor, a new type of material which can observe and control Majorana particles to produce more reliable and scalable qubits, which are the building blocks for quantum computers.

Microsoft believes that, in the same way that the invention of semiconductors made today’s smartphones, computers and electronics possible, topoconductors and the new type of chip they enable offer a path to developing quantum systems that can scale to a million qubits and are capable of tackling the most complex industrial and societal problems.

“We took a step back and said ‘OK, let’s invent the transistor for the quantum age. What properties does it need to have?’” says Chetan Nayak, Microsoft technical fellow. “And that’s really how we got here – it’s the particular combination, the quality and the important details in our new materials stack that have enabled a new kind of qubit and ultimately our entire architecture.”

This new architecture used to develop the Majorana 1 processor offers a clear path to fit a million qubits on a single chip that can fit in the palm of one’s hand, Microsoft said. This is a needed threshold for quantum computers to deliver transformative, real-world solutions – such as breaking down microplastics into harmless byproducts or inventing self-healing materials for construction, manufacturing or healthcare.

All the world’s current computers operating together can’t do what a one-million-qubit quantum computer will be able to do, the developers believe.

Chetan Nayak, Microsoft technical fellow

Photo by John Brecher for Microsoft

“Whatever you’re doing in the quantum space needs to have a path to a million qubits. If it doesn’t, you’re going to hit a wall before you get to the scale at which you can solve the really important problems that motivate us,” Nayak says. “We have actually worked out a path to a million.”

The topoconductor, or topological superconductor, is a special category of material that can create an entirely new state of matter – not a solid, liquid or gas but a topological state. This is harnessed to produce a more stable qubit that is fast, small and can be digitally controlled, without the tradeoffs required by current alternatives. A new paper published Wednesday in Nature outlines how Microsoft researchers were able to create the topological qubit’s exotic quantum properties and also accurately measure them, an essential step for practical computing.

This breakthrough required developing an entirely new materials stack made of indium arsenide and aluminum, much of which Microsoft designed and fabricated atom by atom. The goal was to coax new quantum particles called Majoranas into existence and take advantage of their unique properties to reach the next horizon of quantum computing, Microsoft says.

The world’s first Topological Core powering the Majorana 1 is reliable by design, incorporating error resistance at the hardware level making it more stable.

Commercially important applications will also require trillions of operations on a million qubits, which would be prohibitive with current approaches that rely on fine-tuned analog control of each qubit. The Microsoft team’s new measurement approach enables qubits to be controlled digitally, redefining and vastly simplifying how quantum computing works.

This progress validates Microsoft’s choice years ago to pursue a topological qubit design – a high risk, high reward scientific and engineering challenge that is now paying off. Today, the company has placed eight topological qubits on a chip designed to scale to one million.

Matthias Troyer, Microsoft technical fellow

Photo by John Brecher for Microsoft

“From the start we wanted to make a quantum computer for commercial impact, not just thought leadership,” says Matthias Troyer, Microsoft technical fellow. “We knew we needed a new qubit. We knew we had to scale.”

That approach led the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a federal agency that invests in breakthrough technologies that are important to national security, to include Microsoft in a rigorous program to evaluate whether innovative quantum computing technologies could build commercially relevant quantum systems faster than conventionally believed possible.

Microsoft is now one of two companies to be invited to move to the final phase of DARPA’s Underexplored Systems for Utility-Scale Quantum Computing (US2QC) program – one of the programs that makes up DARPA’s larger Quantum Benchmarking Initiative – which aims to deliver the industry’s first utility-scale fault-tolerant quantum computer, or one whose computational value exceeds its costs.

Quantum partnerships

In addition to making its own quantum hardware, Microsoft has partnered with Quantinuum and Atom Computing to reach scientific and engineering breakthroughs with today’s qubits, including the announcement last year of what they dub the industry’s first reliable quantum computer.

These types of machines offer important opportunities to develop quantum skills, build hybrid applications and drive new discovery, particularly as AI is combined with new quantum systems that will be powered by larger numbers of reliable qubits.

Today, Azure Quantum offers a suite of integrated solutions allowing customers to leverage these leading AI, high performance computing and quantum platforms in Azure to advance scientific discovery.

But reaching the next horizon of quantum computing will require a quantum architecture that can provide a million qubits or more and reach trillions of fast and reliable operations – and today’s announcement puts that horizon within years, not decades, Microsoft says.

Because they can use quantum mechanics to mathematically map how nature behaves with incredible precision – from chemical reactions to molecular interactions and enzyme energies – million-qubit machines should be able to solve certain types of problems in chemistry, materials science and other industries that are impossible for today’s classical computers to accurately calculate.

- For instance, they could help solve the difficult chemistry question of why materials suffer corrosion or cracks. This could lead to self-healing materials that repair cracks in bridges or airplane parts, shattered phone screens or scratched car doors.

- Because there are so many types of plastics, it isn’t currently possible to find a one-size-fits-all catalyst that can break them down – especially important for cleaning up microplastics or tackling carbon pollution. Quantum computing could calculate the properties of such catalysts to break down pollutants into valuable byproducts or develop non-toxic alternatives in the first place.

- Enzymes, a kind of biological catalyst, could be harnessed more effectively in healthcare and agriculture, thanks to accurate calculations about their behavior that only quantum computing can provide. This could lead to breakthroughs helping to eradicate global hunger: boosting soil fertility to increase yields or promoting sustainable growth of foods in harsh climates.

Most of all, quantum computing could allow engineers, scientists, companies and others to simply design things right the first time – which would be transformative for everything from healthcare to product development. According to Microsoft, the power of quantum computing, combined with AI tools, would allow someone to describe what kind of new material or molecule they want to create in plain language and get an answer that works straightaway – no guesswork or years of trial and error.

“Any company that makes anything could just design it perfectly the first time out. It would just give you the answer,” Troyer says. “The quantum computer teaches the AI the language of nature so the AI can just tell you the recipe for what you want to make.”

Rethinking quantum computing

The quantum world operates according to the laws of quantum mechanics, which are not the same laws of physics that govern the world we see. The particles are called qubits, or quantum bits, analogous to the bits, or ones and zeros, that computers now use.

Qubits are finicky and highly susceptible to perturbations and errors that come from their environment, which cause them to fall apart and information to be lost. Their state can also be affected by measurement – a problem because measuring is essential for computing. An inherent challenge is developing a qubit that can be measured and controlled, while offering protection from environmental noise that corrupts them.

Qubits can be created in different ways, each with advantages and disadvantages. Nearly 20 years ago, Microsoft decided to pursue its own approach: developing topological qubits, which it believed would offer more stable qubits requiring less error correction, thereby unlocking speed, size and controllability advantages.

The approach posed a steep learning curve, requiring uncharted scientific and engineering breakthroughs, but also the most promising path to creating scalable and controllable qubits capable of doing commercially valuable work.

The disadvantage is – or was – that until recently the exotic particles Microsoft sought to use, called Majoranas, had never been seen or made. They don’t exist in nature and can only be coaxed into existence with magnetic fields and superconductors. The difficulty of developing the right materials to create the exotic particles and their associated topological state of matter is why most quantum efforts have focused on other kinds of qubits.

The Nature paper marks peer-reviewed confirmation that Microsoft has not only been able to create Majorana particles, which help protect quantum information from random disturbance, but can also reliably measure that information from them using microwaves.

Majoranas hide quantum information, making it more robust, but also harder to measure. The Microsoft team’s new measurement approach is so precise it can detect the difference between one billion and one billion and one electrons in a superconducting wire – which tells the computer what state the qubit is in and forms the basis for quantum computation.

The measurements can be turned on and off with voltage pulses, like flicking a light switch, rather than finetuning dials for each individual qubit. This simpler measurement approach that enables digital control simplifies the quantum computing process and the physical requirements to build a scalable machine.

Microsoft’s topological qubit also has an advantage over other qubits because of its size. Even for something that tiny, there’s a “Goldilocks” zone, where a too-small qubit is hard to run control lines to, but a too-big qubit requires a huge machine, Troyer says. Adding the individualised control technology for those types of qubits would require building an impractical computer the size of an airplane hangar or football field.

Majorana 1 fits into a quantum computer that could be deployed inside Azure datacentres.

“It’s one thing to discover a new state of matter,” Nayak says. “It’s another to take advantage of it to rethink quantum computing at scale.”

Designing quantum materials atom by atom

Microsoft’s topological qubit architecture has aluminum nanowires joined together to form an H. Each H has four controllable Majoranas and makes one qubit. These Hs can be connected, too, and laid out across the chip like so many tiles.

Krysta Svore, Microsoft technical fellow

Photo by John Brecher for Microsoft

“It’s complex in that we had to show a new state of matter to get there, but after that, it’s fairly simple. It tiles out. You have this much simpler architecture that promises a much faster path to scale,” said Krysta Svore, Microsoft technical fellow.

The quantum chip doesn’t work alone. It exists in an ecosystem with control logic, a dilution refrigerator that keeps qubits at temperatures much colder than outer space and a software stack that can integrate with AI and classical computers. All those pieces exist, built or modified entirely in-house, she says.

To be clear, continuing to refine those processes and getting all the elements to work together at accelerated scale will require more years of engineering work. But many difficult scientific and engineering challenges have now been met, Microsoft believes.

Getting the materials stack right to produce a topological state of matter was one of the hardest parts, Svore adds. Instead of silicon, Microsoft’s topoconductor is made of indium arsenide, a material currently used in such applications as infrared detectors and which has special properties. The semiconductor is married with superconductivity, thanks to extreme cold, to make a hybrid.

“We are literally spraying atom by atom. Those materials have to line up perfectly. If there are too many defects in the material stack, it just kills your qubit,” Svore says.

“Ironically, it’s also why we need a quantum computer – because understanding these materials is incredibly hard. With a scaled quantum computer, we will be able to predict materials with even better properties for building the next generation of quantum computers beyond scale.”