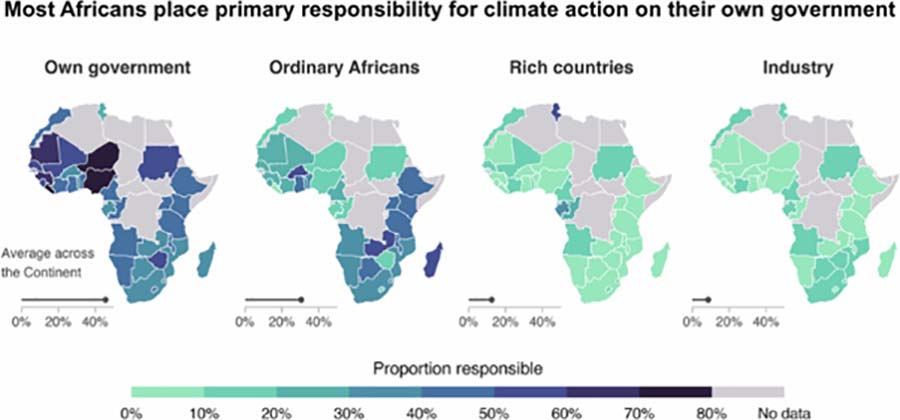

Across 39 African countries, most of those who have heard of climate change place primary responsibility for addressing it on their government, while a further third saw ordinary citizens as most responsible, and very few placed responsibility on historical emitters.

This is according to a study by researchers from the Climate Risk Lab at the University of Cape Town (UCT), published in the Communications Earth & Environment journal.

The research found that education, decreased poverty and access to new media sources were associated with increased attribution of responsibility to historical emitters that contributed most to the cause of climate change.

Dr Nick Simpson, chief research officer at the Climate Risk Lab, who conceptualised and co-led the research with assistant-Professor Talbot Andrews from Cornell University, highlights that these findings are concerning.

He says they also showed that for those with the least capacity to deal with climate impacts, there was a low expectation of any improvement in their government’s responsiveness.

This is important, Dr Simpson adds, because the political salience of climate change themes among political parties and voters remained comparatively low in Africa.

Dr Debra Roberts, who received an honorary doctorate from UCT in 2023, explains that these results are important, as political actors and climate governance stakeholders more broadly will need to pay greater attention to climate action as citizens experience climate impacts, understand its consequences, and increasingly look to hold their representatives and governments to account.

Dr Chris Trisos, director of the Climate Risk Lab, who contributed to the article, sees it as an excellent example of responsiveness to the particular climate change and development challenges facing Africa and the Climate Risk Lab’s global collaboration with long-term partners at Afrobarometer, Cornell University and the University of Reading.

He also highlights an opportunity for change as the findings showed that citizens who have access to resources and information were associated with support for climate action broadly, the empowerment of everyday Africans to act, and the recognition that historic emitters should play a larger role in climate action.

Dr Simpson comments: “Interestingly, state professionalism is associated with citizens’ increased willingness to address climate change, their increased demand that the state also addresses the issue, as well as their willingness to hold the government accountable.

“All three are consistent with the virtuous cycle. In regions with high levels of state professionalism, respondents are more likely to say that ordinary citizens can do something to address climate change.”

The implications

Dr Simpson notes that poverty alleviation and increased access to education, combined with professional frontline government bureaucracies, can re-apportion citizen expectations of responsibility for climate action onto historical emitters and actors with more resources for scalable climate action.

“Future work is needed to identify the joint effects of climate change literacy, the attribution of responsibility, and how the Africans evaluate the action of their governments and historical emitters in addressing or failing to address ongoing climate change and losses and damages escalate.”

Comparison of proportion of respondents in each country who have heard of climate change and believe the actor most responsible for limiting climate change is their own government, ordinary Africans, rich countries, or industry.